Exhibition Review | Paula Rego: Boldness and Surrender

By Ruby Fischer

Milton Keynes Gallery

Salazar Vomiting The Homeland, 1960, Oil on canvas: courtesy of the artist and gallery

Dame Paula Rego is perhaps best known for her large-scale pastel paintings of doll-eyed women in puff-sleeve dresses acting out their dark, folkloric human dramas within the confines of a velvety boudoir or a musty drawing room. She’s known for her rich theatricality, but walking into the first room of Obedience and Defiance at the Milton Keynes Gallery feels like strolling into a fever dream. Gnarled figures and fleshy shapes writhe on their canvases amidst a cut-out chaos of collage and “violent things”. The opening piece, Salazar Vomiting the Homeland shows a blubbery António de Oliveira Salazar hunched over in a corner, a stream of vomit protruding from his mouth in a perfect coil, while a yellow vagina-fruit sporting one enormous hairy testicle and what looks like an ape with breasts look on. In the background, a ship sinks into the blue.

It’s the first in a series of visceral early collages that are her most overtly political, created in response to the Iberian dictatorships in the sixties and seventies. Salazar reappears in The Imposter under a number of guises: pulpous, blue-eyed and many-limbed, dancing with a cloaked figure against a background of pastels and greenery.Throughout, the figures are aerial, flighty and impossible to pin down or define. There is a secrecy in the coded imagery that recalls the dreamscapes of Picasso, Joan Miró and Arshile Gorky.

Born into a middle-class family in Portugal in 1935, Rego studied at the Slade School where she met her late husband, Victor Willing, who, she has said, began their affair by taking her into a room at a party and telling her to remove her knickers. “I did it,” she says, “I always did what he told me, I loved him like mad.” In her life, as in her art, fierce boldness lives alongside devoted surrender.

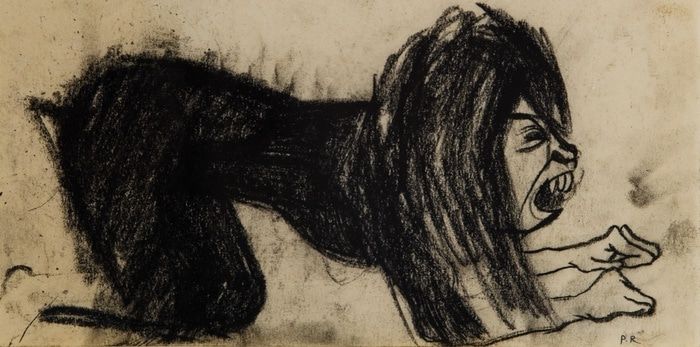

Dog Woman, 1952, Pencil on Paper: Courtesy of the artist and the gallery

It’s a tempestuous combination that finds an unnerving resonance in her Dog Women, who crouch on all fours, bare-knuckled and loose-lipped, both beauty and beast. It’s a slippery metaphor - easily soured in the wrong hands, but Rego insists that “To picture a woman as a dog is utterly believable… eating, snarling, all activities to do with sensation are positive.” And she’s right, there isn’t a hint of caricature in the works. While Rego’s women are often sinewy, angular, sexually aggressive and even cruel, the dog woman with her wide eyes and bared teeth reveals a feral vulnerability that becomes immensely revealing when, in Sleeper, we see her curled up on a man’s coat, her face turned to wall. It’s a deeply poignant response to the death of Vic Willing. Devoid of all the traditional hallmarks of the mourning widow, it is instead a raw, intimate portrait of unguarded devotion to a beloved master, lover and friend.

It’s not all wounded pining, however. Snare shows us what happens when the roles are reversed, and the ailing husband becomes a domesticated puppy, belly-up to the hefty girl who grips him tightly by the front paws, her lips puckered up for a kiss. An upturned crab lies in the foreground, and despite the red rose beside them, the scene is anything but sentimental as the light catches the strain in his wiry frame, ribs exposed beneath her bulk. This canine Willing returns in Two Girls and a Dog, coddled and limp, totally emasculated by the girl nurses who wrangle him into a set of clothes. In the distance, separated by planes of vivid blue and red, a large black dog with eyes ablaze frightens a distant figure, suggesting a longing for a more natural order which existed before virile, predatory masculinity gave way to illness and fragility. It’s not wholly caring or derisive, but an uncomfortable fusion of the two. As with all her work, we are forced to sit in the tenuous in-between.

Untitled No. 5, 1998, pastel on paper: courtesy of the artist and the gallery

Rego’s world is fantastic - dancing ostriches, rabbit masks and conniving maids abound, but out of the storybook canvases of puking dictators and werewolf women emerges the terrifying banality of illegal abortions, which Rego portrays in a stunning triptych which helped to overturn the abortion laws in her native Portugal after the images were published in a newspaper in 2007. It’s difficult terrain that Rego has crossed many times. She recalls a story of a cousin who aborted one of his girlfriends, throwing her body into the sea before she washed ashore, belly swollen with water. The paintings, beautiful to look at with their rich palettes and shimmering pink sheets, show nothing of the gore, but all of the brutality. Lone female figures in empty rooms perch on rickety beds, legs akimbo on a pair of camping chairs; or else squat, hawk-eyed, on a bucket, meeting our gaze with a raised eyebrow. Their lips are closed, their jaws set. It’s an open secret. The setting alone delivers the message, but it’s the detail that drives it all the way home - a ruffled ponytail, a creased uniform, a pair of white trainers beneath socks bunched up the ankle in an after-school jumble. Painted after the Portuguese referendum in 1998, these works carry a weathered wisdom that feels all too necessary in 2019. It Rego’s own words, it’s defiance, “the resolve to survive.”